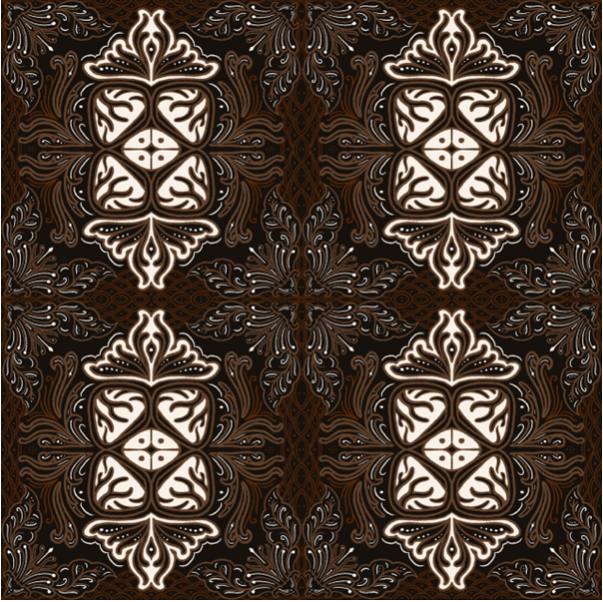

Martinus Dwi Marianto, ‘Looking at Rainbows Through Kluak,’ (55cm x 55cm, direct file transfer on canvas, 2023).

According to historian and Indonesianist, Dr Rob Goodfellow (PhD UOW) “Something happens when we are confronted by authentic novelty.” By this, Goodfellow means, “Something so inventive that there are few clear terms of reference by which to interpret it.” An experience of ‘the new’ is, in fact, rare in life and in art, because almost everything reminds you of something else. For many, this is unsettling. But that is the genius of it. As Goodfellow says, “If interrogated and embraced, new ideas can and do change the world for the better.”

Goodfellow points out that, in the history of modern Indonesia, there can be found an important example of ‘the new,’ namely Pancasila, from the Javanese panca (or five) and sila (guiding principles). On 15 November 1944, Indonesia’s soon to be founding President, Sukarno, gave a speech listing his guidelines for the emerging Indonesian nation. This too was confounding, because Pancasila did not speak of ‘individual rights’ as the American Constitution does, but rather ‘individual obligations,’ namely, a belief in a higher power, the creation of a civilised society, national unity, democracy and social justice. Today Pancasila still exemplifies the disconnect between the rights of free market consumers (individualism) and the obligations of citizens (collectivism).[1]

Professor Martinus Dwi Marianto lived in the Australian city of Wollongong New South Wales for many years with his family while he completed his PhD at UOW. On campus he was exposed to the collectivist ‘Environmental Movement’ for the first time. His recent work ‘Looking at Rainbows Through Kluak,’ (55cm x 55cm, Direct File Transfer on canvas, 2023) builds anew on this experience. (He now teaches at ISI—Institut Seni Indonesia, the Indonesia Art Institute, Yogyakarta.) Marianto’s interest is ‘eco-aesthetics.’ Specifically, his purpose is to create a novel visual narrative in the batik medium to inspire a campaign for the preservation of a threatened tropical spice producing tree, the Pangium edule or Pangium.

My question is: is eco-aesthetics artistic ‘green washing’? Or even, ‘green wishing?’ These are important questions because time is running out for the biosphere with broad consensus amongst the world’s leading climate scientists that human civilisation may have little more than a decade to change almost everything we do, that is, if we want to save the planet as we know it—and save ourselves. Never has there been a greater need for new thinking about conservation. Never has there been a greater need to recognise it when we see it.

Marianto’s project raises a question as old as human civilisation, namely: what is art? Does art merely reflect a world view? Or is there something deeper at play in Marianto’s mind—not interpreting the environmental crisis but rather, transforming our very thinking about it. As Marianto writes, “The beauty of the Pangium is not in its so-called ‘practical benefit’ to human beings but, in the very existence of the tree itself.” Marianto’s statement transmutes our understanding of the Pangium and then, transforms its virtual potential into creative ideas that reflect the existential importance of the species. In turn, we observe Marianto’s idea: to create an accessible visual narrative in the popular batik medium that opens a window into how on we might begin to address the tree’s threatened extinction. Marianto’s work challenges us to reach a greater awareness and understanding of both our natural and human environment as both existential and communal. And, like Pancasila in 1944, the creation of the idea of an eco-aesthetic insists that we change who we think we are.

‘Looking at Rainbows Through Kluak’ is currently exhibited as a one work exhibition at the Public Exhibition Space, the Department of Fine Art, the Indonesian Art Institute, Jl. Parangtritis KM 6.5, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Marianto’s batik creation, ‘Hidden Kawung Crown’ (Copyright, Marianto, 2023) is based on the artist’s understanding of the Pangium fruit (kluak) which imbeds new creative thinking into an ancient art form, namely batik.

A mandala drawn from the octagon of the kluwak and the radiating lines of Pangium leaves (Copyright, Marianto, 2023).

‘Inside-outside Kepayang’ (Copyrtight, Marianto, 2023).

‘Swing Kepayang,’ is formed from the shape of leaves, flowers and fruit ovules of the Pangium, dissected so that the contents are revealed (Copyright, Martainto, 2023).

Peter O’Neill OAM (BA Fine Arts) is an arts administrator, writer and educator with over 40 years’ experience in the development and management of art museums and representative organisations within the cultural sector. His expertise ranges from the initiation and administration of capital programs through to the implementation of sector specific program development and management practices designed to ensure that cultural organisations retain their relevance as evolving social enterprises in a rapidly changing world. Find more here.

[1] Goodfellow, R. et al., (1999). Saving Face, Losing Face, In your Face: A Journey into the Western Heart, Mind and Soul, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 3-4.