Content warning: article contains descriptions of death and injury in armed conflict

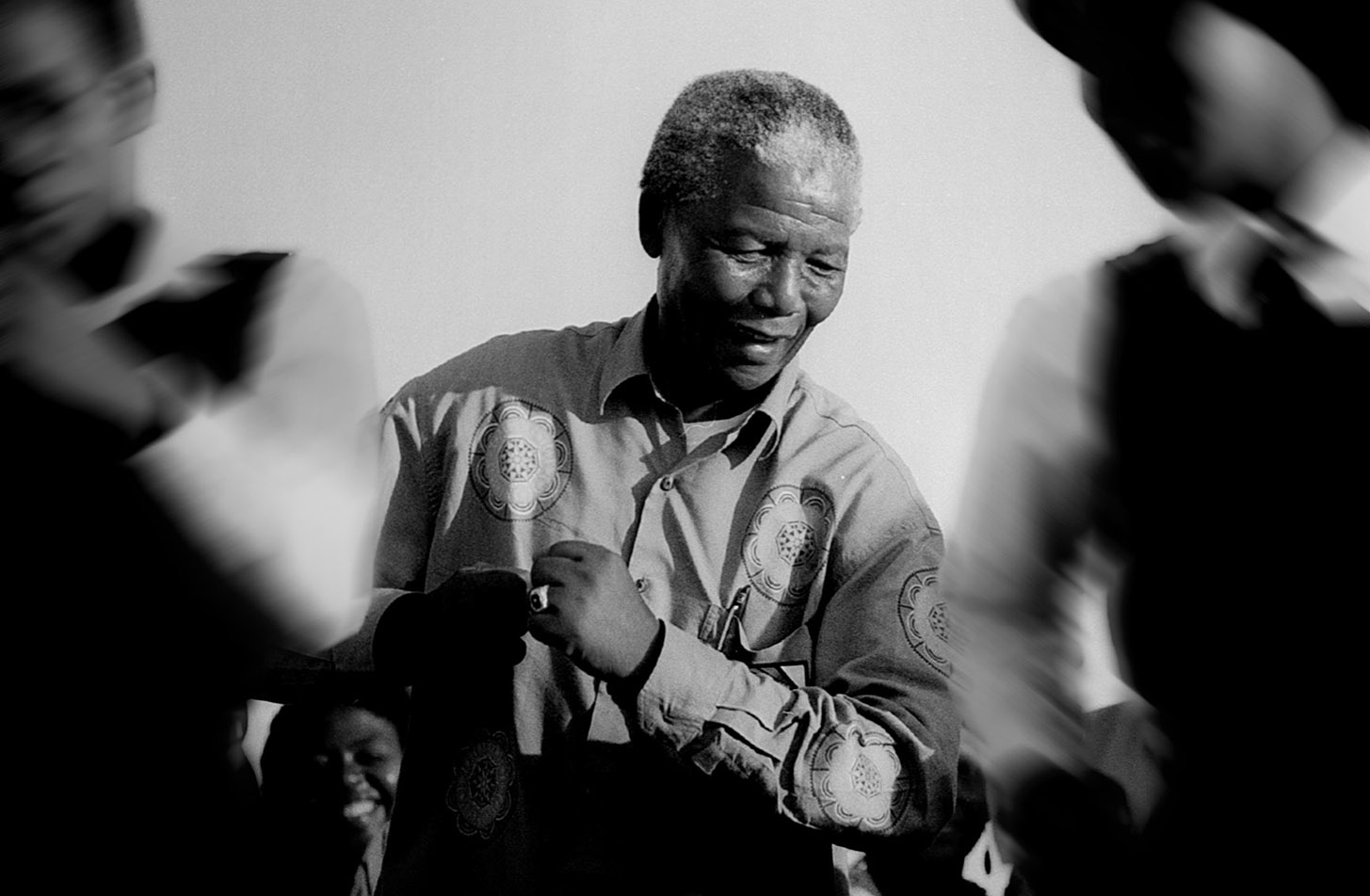

Paul Jones is a photographer, photojournalist and writer. He’s covered it all: Nelson Mandela’s campaign trail in 1994, the Rwandan Genocide, the Second Intifada in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, the recent coup in Myanmar and whale hunters in Indonesia.

I met him one Friday afternoon at Unibar. He asked what I study. Psychology. He replied, “Well, you’re probably the perfect journalist. All journalists are, they’re listeners… The best journalists just let someone tell their story.”

This led to the questions that would define our chat and much of Paul’s work. Paul is someone who has spent a lifetime collecting stories, grappling with the hard questions of journalism. When it comes to war photography, how does a journalist tell a story that is not their own? Can an outsider ever understand what is going on in these conflicts? Who is cut out to record some of the most horrific places in the world? And what is more important: the story or the people behind it?

“It was an electric time in South Africa. I got there in 1993. In April of 1994 was the first all-race election… I was working with Associated Press, we had an office in Johannesburg. I flew in from Sydney and as soon as I got there they said to me, ‘Jonesy, you’re going on parts of this Nelson Mandela’s campaign tour.’ Sometimes we drove, other times we would fly with him in a contingent, following him around.”

“I would just ask, ‘hey, can I jump on that plane with Mandela?'”

“‘Yeah sure.'”

“The thinking went that because I had some camera gear, and I wasn’t from there, that I must have been a journalist.”

As a 22-year-old journalist covering this sensitive and complex period in South Africa’s history, those hard questions about reporting soon appeared.

“It wasn’t just black and white, there were all of these shades of grey in there that I had no idea about. There were African tribes fighting other African tribes and then on the fringes groups of white people saying we don’t like any black people. The Inkatha (Zulu political group) was fighting the ANC (African National Congress). I was just like, ‘what the fuck is going on?'”

Paul was forced to question why he was there and whether he could ever report on these complex events with justice. He asked about war journalism in general, “can you just rock up to a conflict in Afghanistan and just start reporting? Can you give the story justice if you’re there for two weeks, even one week?”

Paul also recounted being told many times he was not the right type of person for war photography.

“I was the wrong person recording it. It took me a while to figure that out. I met some really amazing journalists and photographers… I really admired these people… and a few of them took me aside and said to me, ‘this isn’t for you. You’re not the type of person that should be here.”‘

One of these brutal conversations happened after Paul was caught in the middle of a lethal shootout in Thokoza, a town outside of Johannesburg. “This was a town segregated from their own people. The Inkatha people, who were opposed to the ANC, lived in hostels, these big concrete bunkers. The ANC people lived in shanty towns of corrugated iron.”

“On this particular day, the ANC started firing at the Inkatha people. The Inkatha, from the hostels, started firing back. And then they brought in the South African Army… At the end of the day, you’ve got three sides firing indiscriminately.”

“A few of us (media) got pinned down in the middle of this, behind a wall taking photos, and two guys got shot. The bullet went through the bullet-proof vest of the first guy. With the other guy, the bullet ricocheted off of a wall and went under his armpit and through his neck, missing his vest… So, there was this chaos within the photographers and the journalists and my first instinct was, ‘well we’ve got to get these guys out of here, they’re shot, they’re bleeding out.'”

“I ended up carrying out one of these guys, dragging him out through a firefight to a personnel carrier. I said, ‘we’ve got to get this guy out of here, we’ve got to get him to a hospital.”‘

“While this is happening, there are other guys photographing… They’re nice people, but their first instinct was to photograph because that’s what is most important.”

“So, when I got back to the Associated Press office they said, ‘so, where are the photos?’ And I was 22, you know, I didn’t get any. They said, ‘your job is to take photographs.'”

“Did I miss the picture? Yes. And that was one of those points where someone took me aside and told me I wasn’t cut out for this.'”

That incident was the beginning of the end of Paul’s time with AP and covering South Africa. He went to Israel because he felt “like I had something in me.”

But the same ethical problems kept coming up. Did he really understand what was going on? Was he the right person for the job?

“I went there with a pretty closed mind of like, ‘yep, I’m pro PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organisation), I’m pro Yasser Arafat (Palestinian political leader), I’m pro-Palestinian state, I’m anti-Israeli state.’ Then when I got there, everything got thrown out of the window. I met left-wing Israelis who were like, ‘let’s all live together, call this state whatever you want.'”

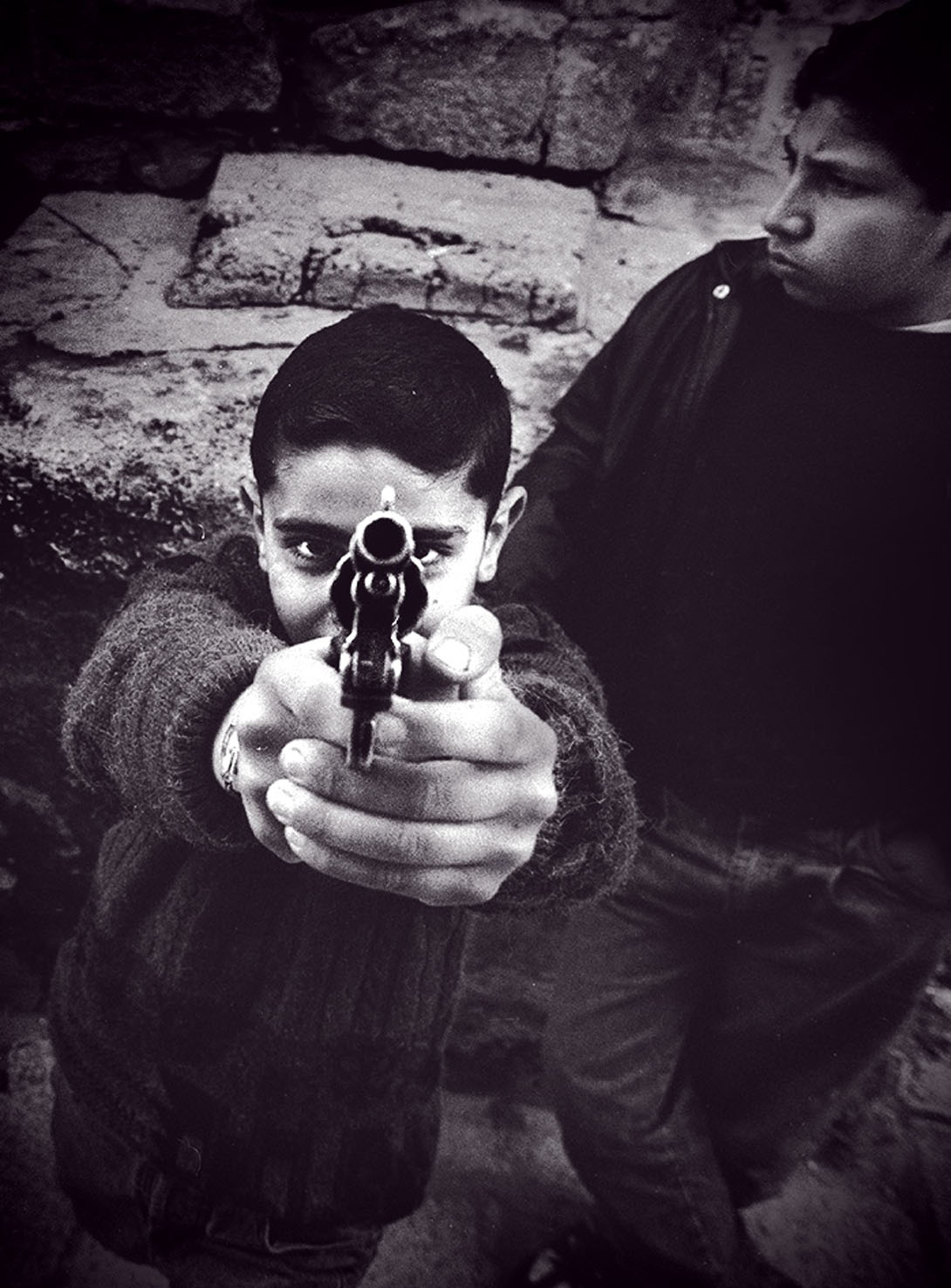

“Then I went and photographed Hamas (Palestinian Sunni militant group), who were training kids to be suicide bombers. They had them all strapped with mock up explosives, and a bus made out of cardboard, and they would be instructing where the guy should stand in this bus to kill as many people as they possibly could. I thought, “‘these guys are nutcases, but they’re also Palestinians, so where do I stand here?”‘

“The longer you stayed there the more you realised that there was no black and white, there was a whole lot of grey… But that was the role of the journalist, to document that. To document what was going on from both perspectives.”

And then there was the issue of being the ‘right person’ for war reporting. Increasingly, it became clear that being the ‘right person’ depended on what you did in the crisis situations that are everywhere in war photography, in those fight, flight or freeze situations, as Paul puts it. Do you rush in to help or do you take the photo?

“‘It was the same in Palestine. A mate of mine, he was a Palestinian and he had been a refugee in Jordan and became a journalist. He got shot in the neck. It was in a skirmish between the Palestinians and the Israeli Defence Force. I got caught in the firefight, I couldn’t do anything for this guy, he just bled out in front of me… I took him back home to his family. Then I took pictures, pictures of him laying out and his mother and father crying, but even that felt weird to me. Like I know this guy, why am I taking photos?”

“I went back that day just really assessing. What was I doing here? And it went back to people all along telling me you’re not the right person for this job. I was thinking, maybe these guys have been right all along. Maybe I’m not the right guy for this job.”

I asked him about the people who are cut out for it, what they are like.

“They do switch off a certain part of their thinking, where they go, ‘I am here to witness, I am here to document.’ And that in itself, it’s a fight or flight mentality of what do you do: do you take a photo and then help someone? That’s not the way I was thinking.”

It seems Paul has brokered an uneasy peace with these ethical and personal concerns with his current work. He recently documented the coup in Myanmar, where he used a very knowledgeable local contact to inform his reporting. As for whether he was the right guy, in this case, that wasn’t an option: “If I don’t report on it, who will?… We don’t hear about it in Australia.”

He has also written recently about whale hunters in Indonesia and has made a very conscious effort to stay away from what he calls ‘parachute journalism.’ “I just wanted to document these people and write about what they do. But to do that, to give them the true story, I went back and forth from that place for 5 years. I’m still going backwards and forwards. There’s just no way staying there for a month that I could’ve understood. There’s no way you can understand a whole culture in a month. But after five years you learn the people, a bit of the language, they expect you there at certain times of the year, you understand the society and how the society works. And then I saw it and wrote about it in a whole different light, because I actually started to understand.”

*All photos curtesy of Paul Jones