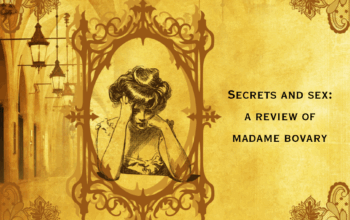

The Quaint residence abides around a cold street corner at 92 C Gosemer Rd, Meralvile, where tall apartments tower over a red door. The porch angles so slightly to the left, leaving an embellishment of chipped paint on its corner where the timber meets the concrete. This is where Mrs Quaint returns home in the dusk of a Friday evening to drop her shoulder against the door as she rattles the key in the lock to wedge it open. She grapples with her sliding cotton scarf and lanyard and bag of papers as she trudges indoors, leaving the frozen street

and the long week behind her.

Inside waits the ghost of her husband of eight years. He dwells in cursive handwriting on the desk in the study, abides in the gravelly voicemails within the telephone and nests in the button up shirts draped on dining chairs by the fire.

He is yet to return home.

Camilla Quaint storms into the kitchen to retrieve a knife. Sliding a cutting board onto the bench, she plucks a pomegranate from the fruit bowl and splits it, spilling its bloodied innards to scrape into a small bowl. She pries from the back of the glass cabinet a porcelain plate and

arranges within its blue ring a quarter block of brie, salty biscuits, chocolate and orange slices. Carrying platter and bowl and bottle of wine upstairs to the bedroom, she places the ensemble by the bedside and strips her heels and bra from her body, rubbing the red lines the

seams have made on her pale skin. Beneath the duvet she sits cross-legged with her spine straight against the bedhead.

Her husband will not return tonight. This is getting too familiar. The long day of work will become a long evening of housework and a longer night alone. He is elsewhere, occupied by other things. Camilla pulls the cork from the bottle and brings the neck to her lips, sipping slowly. This brings clarity. She will not bother to prepare a meal for it to grow cold on the dining table. She will close the shutters and stoke the fire and eat from this platter in bed until she has read a novel from cover to cover, for however long into the night it will take.

A big butterfly has blown in through the open window and now flaps in orange gyres above Camilla’s face as she lies beneath the covers, hapless under the weight of the impending day. Her head aches as she shifts to her side to squint at the daylight, perplexed as to how the

window has seemingly opened itself overnight. An empty bottle of wine is on the bedside table. She pushes it aside to rummage the cheese knives and biscuit crumbs away, retrieving her pocket watch. Her husband will be home around midday and expecting lunch, as is his

habit of neglect. She doesn’t have much time to get ready.

Lurching from the bed, Mrs Quaint shakes the covers out smooth and tosses the pillows in place before tumbling downstairs in her robe. Inside the hearth, the fire has settled into a bed of cold ash. The laundry pile lies dejected and shivering on the cold tiles of the

laundry. The ice box is empty. The kitchen is without bread or eggs. She must go into town. Mrs Quaint throws a mauve silk over her tangled hair, dons her sunglasses, and turns to address her reflection in the mirror. This blazer has a toothpaste stain on the collar. It will have to do. She shuts the door to the bedroom.

The street is quiet with a Saturday absence of mind. Camilla’s trek through the snow leaves a trail of size seven boot prints in the snow behind here, ink dark against the glare. Her journey is mapped for all to see, the near-empty town witnessing her plan unfold.

The bank teller’s eyebrows are pinned ever so slightly upwards at the ends by a distain for her request. She will open an account in her own name and will transfer £15 000

out in cash, as per her husband’s request in writing. As the teller makes a phone call, she

inspects the bulging envelope, turning it over with her polished fingernails before sliding it

into her handbag.

“Thank you kindly,”

The bell above the door rings triumphantly as she exits, elated by the act of theft. This rush is addictive. Her hands are itching red with guilt which weighs nothing on her conscience.

Camilla dumps her grocery bags in a street-side bin, resolving now that her prints in the snow cannot be undone. She will see this path through to the end. She will not buy groceries this morning, nor do the laundry, nor re-light the fire. She will claim this house that

she has laboured over for a lifetime as her home, in her own right.

She utters this justification like a mantra as she walks home, cradling two black greyhound puppies under each arm, tucked beneath the folds of her long coat. She has always desired to keep pets. Her husband wanted nothing to do with them. These dogs she will train

to guard the door. Their curly black ears bounce as she struts home. The siege has begun.

Adrienne is in her third year studying a Bachelor of Arts (Writing and English Literature) at UOW. She moved to the Illawarra from the Central West to develop her skills as a writer and textiles artist. She writes short fiction pieces for the Tertangala in poetry and prose form. Her work is underlaid with a witty commentary on the shared experiences of the pandemic, student life and moving from home. Using threads of these common themes, she aims to weave connections across environments and communities.

Image: Anya Smith/Unsplash