Image: Studio Ghibli

Reflecting on Hayao Miyazaki’s first masterpiece Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, with the climate crisis on my mind. This article contains spoilers.

Perhaps you may or may not think about this often, but the reality is that we are currently living in a world edging towards the collapse of the ecological foundations that sustain life on this planet.

Australia and climate disaster

In February, 38 scientists from 29 universities published a report in the well respected journal Climate Change Biology. The report examined the welfare of 19 ecosystems: from the Australian continent to the cold plains of Antarctica. What they found was that all ecosystems studied, including the tropics of the Great Barrier Reef and the lifeline that is the Murray Darling River, showed clear and consistent rates of ecological collapse and species loss in the last 30 years. They concluded that the deterioration is the result of climate change and other human inflicted activity like pollution, the destruction of natural environments in the name of capital and so forth.

What’s more concerning is that the same report states that the rate of environmental deterioration has only became more severe and expansive in the last decade, lining up with the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO) recent findings. WMO found that 2020, despite the world almost coming to a standstill with the pandemic, was one of the three warmest years on record as the burning of fossil fuel only decreased by only a measly 7 per cent. With the destruction staring us down in the distance and the devastating events of the Black Summer bushfires barely out of the rear view mirror we are left to ask ourselves: how do we handle our role in the survival of not only humanity but of all living things?

Last month, the Morrison government announced that they will be spending $600 million on a new, yes a new, gas-fired power station in Kurri Kurri in the Hunter Valley. This served as one of many slaps in the face to all those who are calling for Australia to implement policy for our transition to a 100 percent renewable grid and a net-zero emissions target by 2050. Not only does it make no economic sense, with the head of the government’s Energy Security Board Kerry Schott saying that there are much cheaper, cleaner alternatives, but also the fact that gas contributes more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere than burned coal when counting the methane that escapes during the extraction process.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison, when questioned about the government’s justification for the project, gave a rather shallow response saying that “wind doesn’t always blow, [the] sun doesn’t always shine and you need therming power from gas to ensure [that] renewable energy investments are effective”. What he failed to mention of course was that battery storage technology has developed to the point where we can confidently start building widespread infrastrastructure, for example last year the UK government gave the go ahead for a 320 megawatt battery site to start construction in London.

Most worryingly the Prime Minister’s remarks may serve as a part of strategy signaling to voters that it is not worth transitioning to renewables quickly. That we are simply saving jobs in the minerals industry: what do we need to worry about? The Morrison government has decided, based on my own observations in the two years since the last election, that in a time of an environmental crisis: what is the point of changing our ways to care more for welfare of the environment? What is the point in trying to understand the natural world? What is the point in recognising our role in it?

Nausicaä and environmental catastrophe

That brings me to Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki’s 1984 film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Miyazaki’s second feature film, based on his 1982 manga of the same name; takes place in a post-apocalyptic future, set a thousand years after a catastrophic event known as the Seven Days of Fire nearly wiped out nearly the entirety of human civilisation and led the earth’s environments to collapse into forests of toxic spores, inhabited with giant mutated insects. In this world the remaining humans live in small, warring kingdoms on the outskirts of this ever expanding forest, referred to as the Sea of Decay (or Toxic Jungle in the English dub). It is here that we follow the titular character Nausicaä, the young princess of the safe haven the Valley of the Wind.

Hayao Miyazaki took inspiration for Nausicaä from various contemporary and historical texts. Most notably modelling his protagonist after the one seen in the Japanese Hein folktale The Lady who Loved Insects and the Greek goddess described in Homer’s Odyssey of the same name. Frank Herbert’s Dune and Brian Aldiss’ Long Afternoon of Earth also served as inspiration for elements of the world Miyazaki created; however, the very real life event that inspired him to create it in the first place was Japan’s Minamata Bay disaster.

Minamata was a factory town located in Japan’s southern island of Kyūshū which by the second half of the 20th century had become the nation’s leading chemical producer with the factory operated by the Chisso Corporation, being the crown jewel of the local economy. However, for all the financial prosperity that came with the chemical production also came at great cost to the surrounding environments, resulting from water and air pollution from the factory’s waste.

By the early 1950s, the local fishing industry began to notice strange patterns: the number of fish caught by the 200,000 strong workforce had decreased dramatically with marine life found dead along the shores and the cats from the fishing villages developed spasms and blindness; with some even running into the sea to die. Despite these concerning signs neither the Chisso factory or city administration paid any attention to them. With that, the factory continued to dump an estimated 600 tons of mercury into the wastewater that led into Minamata Bay. This environmental neglect would also bring tragedy to the human population.

In April and May of 1956, a neurological disease began to appear amongst the population caused by eating market fish that, unbeknownst to them, had been poisoned by the mercury. Patients developed severe symptoms including violent muscle spasms, inparied speech and eyesight and ultimately death. Soon enough, with this epidemic now known as the Minamata disease, many locals and professionals and even higher ups at Chisso connected the dots.

However, instead of listening, Chisso, and the government agencies simply ignored their concerns, dismissing the matter to the point where they did not cooperate with investigators and increased their production over the next decade. It wouldn’t be until 1968 that Chisso finally closed their factory in the region. It wouldn’t be till then that the Government finally officially recognised that the Minimata disease was caused by their neglect and 112 people, including patients and their families, sued Chisso for 642 thousand Japanese yen (or roughly AU$28 million in today’s money). Since 1956 officially 2,995 people have contracted Minamata disease with 1,784 passing away from complications.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind encapsulates a lot of the themes and interests that Hayao Miyazaki would explore time and again throughout his career; pacifism, anti-war sentiments, feminism, aircrafts. But it is the relationship between humanity and nature that serves as the main driving force of the narrative. In a memo written to the crew during pre-production in 1983, Miyazaki makes his intentions for the film clear:

“For the past few years I’ve put forth ideas for film projects with the following ethos. To offer a sense of liberation to present day young people who in this suffocating, overprotective and managed society find their path to self reliant independence blocked and therefore have become neurotic; a major theme of this work is the manner in which people engage with nature, the nature surrounding them upon which they are dependent; can hope, exist even during this twilight era.”

Hayao Miyazaki, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind pre-production 1983

These days I tend to watch post-apocalyptic films through an eerie lens: what does this film do for the soul in such uncertain times? Remembering that we are indeed approaching some kind of end.

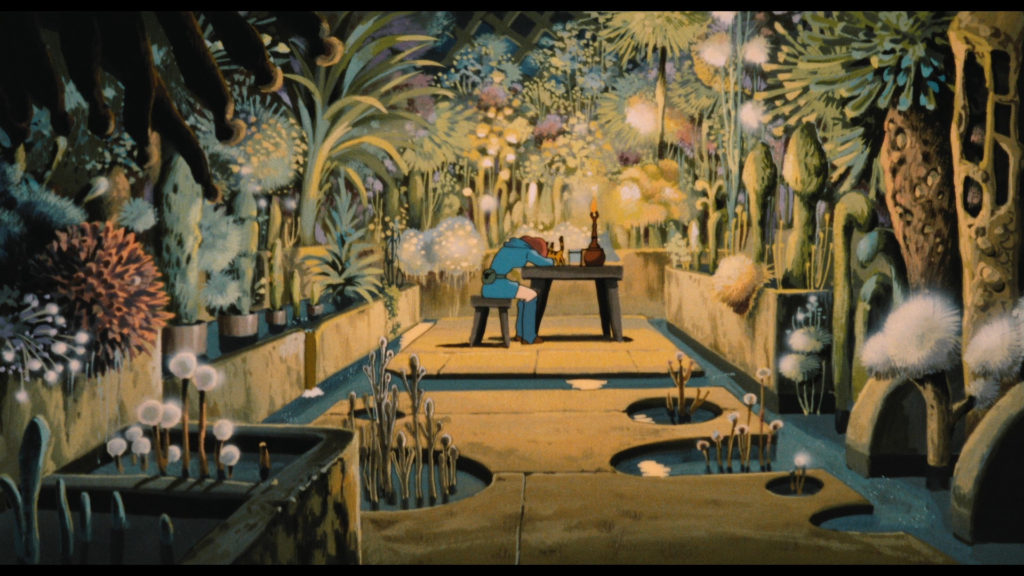

Watching the first sequence where we meet the titular character Nausicaä as she explores through the Sea of Decay, in what we can assume is a trip she’s done countless times before, you can’t help but feel invited to view the Sea of Decay through the same wide eyed amazement as she does. It is a place teeming with natural wonders, in spite of the danger this is a place worth understanding forensically and perhaps even spiritually.

In an action-packed film, one of the best and perhaps saddest moments comes when Nausicaä takes a minute to look up at the toxic spores falling from above like snow and from behind her face mask (how relatable) realises that without the air of this beautiful place is toxic enough to kill her but still she rests and takes in the world around her. I’m sure that many of us have had a similar experience walking our way alone through nature, looking up and thinking about our place in the world.

Nausicaä, as a character displays a clear compassion for all living things: to the villagers of the Valley of the Wind and the mammoth insects of the Sea of Decay. Embodying the principles of Miyazaki’s outline, she actively engages with the natural world surrounding her and recognises the Sea of Decay as not a place to be fearful of but rather a place where it’s inhabitants’ welfare is as important to that of humans and that peaceful coexistence with the environment is integral to human life.

Some of these positions embodied by Nausicaä extend to her kingdom of the Valley of the Wind. In the film we see that the village harnesses the gusting winds that blow through the valley as a natural resource, using large windmills to pump water from the earth and caring and maintaining the forest that is perhaps the closest green reminemt of the world before the apocalypse as it helps life in the valley to prosper as an agrarian community.

As for the source of conflict in the film, it is very much intertwined with humanity’s relationship with the environment and the motivations and moral positions of the antagonist the Tolmekians (predominantly) and the Pejites. They are coded as imperialistic but this is by no means black and white; with them presented as misguided and fearful rather then strictly evil. The Tolmekians and Pejites may be warring against each other but the truth is that their goals are almost exactly the same: to eliminate the expanding Sea of Decay and the insects that inhabit it so that humanity may prosper once again. For the Tolmekians especially, led by their leader Kushana, they aren’t motivated by pure malice but out of desperation to protect themselves. However, in trying to position humanity as the dominant force over nature only manages to cause more violence, death and suffering whether it’s between humans and the natural world or humans and each other.

Now, coming back to compare the actions of the Tolmekians and Pejites to the previous real-life examples, you can draw a thread that perhaps brings these three loosely related scenarios together. The actions of the Morrison government, the Chisso Corporation in Minamata and the Tolmekians and Pejites in Miyazaki’s film aren’t driven by some sadistic scheme but by delusion, greed and fear.

For the Morrison government there is absolutely nothing stopping them from implementing policy that will help combat the very-real threat of climate change and the collapse of Australia’s environments except themselves. They prefer to expand the capitalist frontier of fossil fuels, whilst someone out there will reel in a hefty amount of money, it will ultimately come at the cost of further deterioration of all natural life. Last week, Scott Morrison even told a conference of executives from the fossil fuel industry that oil and gas will ‘always’ be a part of the Australian economy. Tragically for the people of Minamata, the actions of Chisso’s environmental neglect had already caused a great deal of suffering to the people and environment and rather than responding to the issues they’d created they chose to ignore them preferring to protect themselves.

But of course, there is still hope. Today, the environment has been pushed close to the brink of destruction by our detrimental actions leaving the planet fighting to sustain life; however, that doesn’t mean that we should just succumb to the pressures of heading towards the end of sustainable life and believe that there is nothing we can do about it.

Even though Hayao Miyazaki has said to be a pessimist when it comes to his views on humanity’s future it would perhaps be a mistake to say that he doesn’t believe there is something we can do about reconnecting with the natural world and finding a way to coexist peacefully and sustainably with the environment by looking at his work. In Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Miyazaki proposes that even in a world where the environment has already collapsed into a place that is almost uninhabitable for human life that we still have a responsibility to engage with, care for and depend on nature for the welfare of ourselves and for future generations. It’s enough to help relight the spark of the environmentalist within ourselves, with a heroine who has perhaps inspired at least some climate activists out there in some way.

Whether you’ve never seen Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind or haven’t watched it in a while I highly recommend you go and check it out (it’s currently on Netflix). I’d also encourage you to at least give the original Japanese dub a try since I personally think the dialogue in the subtitles is just a little bit sharper than that in the English dub, however watching it in English is great as well (with the only notable difference being that the Sea of Decay is called the Toxic Jungle).

I watched Nausicaa earlier today and then somehow managed to stumble upon this article! It’s pretty much impossible to watch the film without thinking about our current climate change situation in Australia. Very interesting read